The short film Split Lives (2021) by Joshua Bolchover and John Lin, winner of the Transfer architectural video competition, recaptures, through the testimonies of its inhabitants, the peculiarities and challenges of life in the underground houses (yaodongs) of the Xizhang village, near the city of Sanmenxia (Henan province), China.

Yaodongs, as a context, result from an ancient tradition spanning millennia, where rural communities worked together to construct homes for each family. This collective effort made the construction process more manageable, strengthened the social fabric, and helped forge the villages' identities.

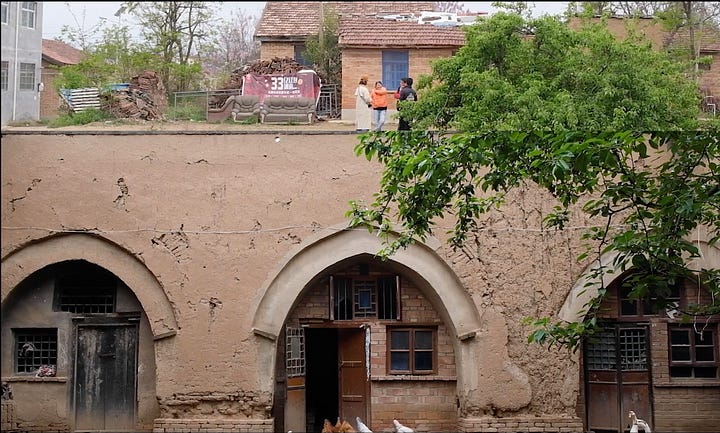

The scarcity of certain natural resources in the area, coupled with extreme climatic conditions, led the inhabitants to innovate in their building techniques. By using clay as the primary material and constructing the homes underground, they created the efficient structures that remain today.

These houses feature a central courtyard, the only source of light for the dwelling, with its four sides forming the exterior walls. The interior rooms have a rectangular floor plan and arched ceilings, while the surrounding land was used as family farming plots.

Through the polyphony of voices in the short film, Bolchover and Lin illustrate how contemporary urbanization is rapidly transforming the ways we inhabit spaces, using Henan's yaodongs as an example.

Driven by demand and economy, new rural housing architectures globally follow a homogenizing model in both design materials and functionality. This model is displacing and destroying traditional forms of construction and the reproduction of community life.

In its brief five minutes, we hear testimonies like that of Zhang Jian, secretary of the Fan branch of the village, who tells us that the population is 3,155 inhabitants and whose main industry is apple cultivation. He also informs us that before 1998, there were 341 underground houses, of which only 16 remain today (11 of them were preserved and renovated thanks to government subsidies).

We also hear from an elderly woman who recounts that her children and grandchildren live in Sanmenxia, leaving their three acres of farmland empty, thus highlighting the transformation in life expectations from one generation to the next.

Another male voice offers more details about the structure of the underground houses, explaining that the larger and deeper rooms are generally used as bedrooms, the shallower ones as bathrooms or storage rooms and that the kitchen is usually in the central courtyard.

Several other voices point to the growing depopulation of the countryside, migration to cities, and the transformation of rural homes, which have shifted from the family house as a center to multifamily apartments.

These radical changes in ways of living, in addition to posing challenges for architects, urban planners, and primarily the affected communities, also offer a great opportunity to rethink how we live and relate to each other.

This invitation to question our ways of life is ultimately the central axis of the short film.

The film creates tension and highlights the dialectic between the past and the present, between traditional and generic construction, which is expanding globally under the banner of modernization. It shows the complex and intertwined relationship between the rural and the urban, a nexus that defines the peculiar physiognomy of the contemporary Chinese landscape.

In 2011, the Chinese government declared yaodongs an intangible heritage, initiating a conservation plan that has materialized in economic aid for the maintenance and remodeling of the homes, including services such as running water and electricity. In this new reality, tourism emerges as a means of survival for these rural communities, and the local government of Henan is doing its best to incentivize it.

However, the directors propose several alternatives to tourism as the only path to integration, thus enriching the simplistic discourse that associates the material conservation of places with the protection of the social practices that gave them shape and reason for being.

At the end of their piece, they suggest that architecture can become a way to transform spaces instead of merely reinventing them. Urbanization strategies can be based on the organic evolution of places rather than their disintegration. Housing construction can be reclaimed as a collective act that creates and reproduces community, instead of a practice that must be outsourced.

Ultimately, the emergence of these evolving rural-urban spaces harbors the potential to offer novel perspectives on life and living.

In essence, it serves as an invitation to reconsider our modes of habitation and to reexamine our concepts of development and modernization.